|

(Theropithecus gelada)

Amharic:

Gelada

The Semyen

highland massif is considered to be the finest scenery in all Africa and

it is for this reason, and the fact that the area is the home of the

Walia Ibex, the Semien Fox and the Gelada Baboon that it has now been

gazetted as a national park.

The Gelada is not

in fact peculiar to the Semyen as is the exclusive Walia Ibex, but they

are more numerous here than in their other habitats Some live at Debre

Sina not far from Addis Ababa and others at Debre Libanos on the way to

the Blue Nile; there are also small populations in the Mulu and Bole

Valley gorges. But in the Semyen there may be as many as 20,000, and

troops of 400 together may be seen. They do not molest humans and, more

surprisingly, the local people do not molest them. Thus they are very

tame and will allow humans to approach quite close to the troop before

moving nearer to the cliff edge.

The Gelada was

discovered in 1835 by the explorer Ruppell, who nan;ed it by the local

name used by the inhabitants of Gonder region where he first observed

it. They are not difficult to study as they are very tame, however,

little interest was shown in them until recently, when Patsy and Robin

Dunbar made an exhaustive study of their social behaviour. The social

behaviour of the apes and monkeys is evidence of a very high degree of

intelligence and studies of their rudimentary social structures are

proving of considerable value in analysing the origins of human social

behaviour.

Geladas live

along the edges and steep slopes of precipices. They never move far from

the rim and thus their distribution is linear along the escarpment. At

night they climb down the steep cliff faces to caves where they roost on

ledges, often huddled close together for warmth as Semyen nights are

frosty and bitterly cold. Babies cling tight to their mothers even in

sleep. In the morning in the warm sun they climb up again to the top of

the cliff and spread out to feed. Geladas are mainly vegetarian, living

on herbs, grasses and roots, but they also eat insects and locusts. They

never eat meat, or hunt or kill even small birds or mammals. As a result

of this restricted diet they are obliged to spend a very high percentage

of their lives foraging and browsing in order to obtain sufficient

nutrients to survive. This may explain why they are so extremely

peaceable by nature, with very little squabbling even amongst

themselves. They have no natural enemies (except of course, Man, who

takes a fair toll with his rifle. The great mane of the adult male is

used for traditional headresses by highland warriors).

Apart from

feeding, "grooming" is their other main pastime. This entails simply

picking through each other's fur. This is not only a friendly and

peaceful occupation, but it serves also to establish bonds between

various members of a 'harem' and to cement the accepted relationships in

the hierachy, between male and female, older and younger members.

The long narrow

plateaus of the Semyen slope up- wards from the south until they end in

the dizzying precipices of the northern escarpment. This is the haunt of

the Walia, and the Gelada do not frequent these vertical cliffs, but the

rims of the stupendous gorges and ravines which bisect the plateau. The

troops tend to graze the higher moorlands, amongst everlastings, giant

lobelias and alchemilla-tussock grass. Never far from the rim, which is

their refuge when danger threatens, they disappear over the edge on to

the grassy slopes and ledges of the gorge sides. Their grazing ranks are

so arranged that the males are always farthest from the edge and thus it

is "women and children first" when they have occasion to flee to safety.

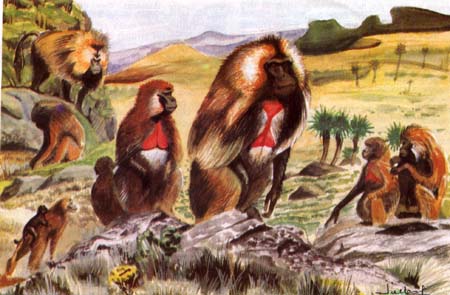

They are

comparatively large and impressive, the males being about 75 cms. (30

inches) tall without tail and twice the size of the females. Their sad

up- turned faces are marked with large ridges running from below the

outer side of the eyes to the nose. The face is dark grey with wrinkles

and very long whiskers, forming falciform tufts of light coloured hairs

projecting upwards and backwards on the sides of the head. Their

nickname, "bleeding heart baboon" stems from the bare red skin areas on

the chest, which are actual]y two triangles, and another crescent-shaped

on the throat. Both sexes have these bare places. In the female the

fleshy "beads" which surround the bare patch swell up and turn from

whitish to bright red to indicate estrous condition. In the males the

patches are always red and do not change colour. The old males have a

cape of very long hair which hangs down (to the ground when they are

sitting) and tufted tails which have earned them another name - lion

monkey. The female's mane is much less impressive than the male's. Both

sexes are a light to dark brown, the fur cape shading from one colour to

another as it moves in the mountain breezes. They are found at more than

4,500 metres (14,600 ft.) and have even been seen at the top of Ras

Dashan at 4,620 metres (15,160 ft.) where tbere is nothing fox them to

eat, so they must just go up to look at the view.

Their handsome

appearance and the beauty of their habitat is one thing, but perhaps the

most fascinating aspect of these creatures is their social structure

which is the most complex in the animal kingdom after that of man. You

see them grouped into herds of up to 400 or so individuals, each of

which is made up in turn of "harems", which are groups of from two to

eight females and young ones with one dominant male and often one

hanger-on called a "follower", who ingratiates himself with the juvenile

females, with a view to enticing them away in due course and forming his

own harem. Harem owning males do not attempt to steal each others'

wives.

Young males get

together in groups from the age when they finally leave their mothers

until they are mature enough to become a follower. These various social

groups all move and feed together, only occasionally leaving the herd if

food supplies demand it. They travel about three miles a day while

feeding, and sleep on ledges on the cliff face wherever they happen to

be when night falls.

The harem is a

very close family unit. Ninety-five percent of the social interactions

of adults are with other members of the same harem. Only juveniles and

babies cross the invisible boundaries to play with others of their own

age. Unlike the Hamadryas baboon, where the harem is kept together by

male agression, the Gelada harem is run more or less by solidarity

between the females. It is they who decide in which direction they will

feed, it is they who instantly rally together if their male should

threaten any one of them because she strayed too near another male! Only

one of the females has a strong relation- ship with the male at any

given time. But they all groom each other as well as him and thus

establish a jealousy-free harmonious relationship with each other.

For a young male

to acquire a harem of his own is quite a long and difficult process. He

starts off when he is about two leaving his mother's harem in favour of

play groups of other juveniles. By the age of three he starts playing

around with the younger members of the all-male groups, and at four he

things of nothing else but joining one (which is not always easy as the

groups are very tight and do not readily welcome new members). Having

succeeded he settles down to life as a bachelor sub-adult in his group.

When he is about five or six, he begins to show an interest in the

harems again. He doesn't want to anger the adult male of any harem so he

confines his activities to following along, occasionally grooming with

the male but mainly amusing himself with the young females - the ones

too young to cause jealous feelings in the old male. Should the old male

die or become weak, the young one will take his place, but it is more

common for the youngster just to gradually withdraw taking with him

several of the young females. This is not a sudden break - the one group

just spends progressively more time on its own. The male then sets about

getting a few more females from other harems - young females belonging

to a harem with no follower may join him before their father takes an

interest in them.

Over the years

each male has a succession of followers who take away his daughters to

form the nucleus of their own harems; a system which prevents in-

breeding. Sometimes a younger male may persist in paying court to the

wives of an older, and generally harrass him. The few fights which occur

are usually the outcome of such behaviour. The old one finally, after

trying to retain his females' loyalty and affection, may give up the

struggle. If so, he does not retire from the harem - he just adopts the

follower role and spends his retirement grooming and playing with the

juveniles.

The relationships

of the Geladas are very delicately balanced. To communicate their

intentions they have need of a fairly subtle range of signals. They have

therefore acquired a great diversity of social behaviour patterns and

vocalizations. Greater in fact than any other non-human primate. For

examp]e, where the olive baboon has fifteen contact calls, and the

colobus six, the gelada makes twenty-seven distinct noises. To hear him

speak, is as it were to listen to a foreign language being spoken. The

expressions on the face are in fact signals with a distinct meaning: the

raising of the eyebrows reveals two red triangles above the eyes - a

warning signal; the rolling back of the upper lip in a ghastly smile, a

flash of red gums and white teeth, signifies (as perhaps does the human

smile) appeasement, and thus avoids possible conflict.

So far, the

gelada is not on the endangered species list, and now that he lives

protected in at least one of his habitats, one can hope that he never

will be. How- ever, the occasional random slaughter "for fun" of these

beautiful, gentle and intelligent creatures should be curbed for obvious

reasons. |